Published: Updated:

Old-school scammers are trying to get back in the (con) game and, surprisingly, they’re doing it via snail mail. Here’s what you need to know about the inheritance scam, delivered straight to your home by the USPS.

I was intrigued when I discovered a letter in my mailbox from an anonymous P.O. Box in Montreal. The envelope, addressed to my husband, had his name strangely typed in all capital letters. It immediately gave off a chain-letter vibe, and my scam detector went on high alert.

The envelope contained what can only be described as an old-school inheritance scam from a different era — before the digital age.

As I read the letter, I almost felt sorry for this particular scammer. Instantly, an image came to mind of a long-past-his-prime fraudster desperately trying to stay relevant among modern swindlers.

Despite the Montreal return address, this sloppy con-artist said he was writing from his law firm in Ottawa, Canada. “Peter Bruno” further demonstrated his geographic confusion by bizarrely including Toronto in the date field of his letter.

A quick scan of the message revealed a long, convoluted tale meant to confuse the reader. But the upshot was that my husband would soon be inheriting $11,550,300. Luckily, there would be no “associated risks,” and the scheme was all legal, the author assured.

As I walked back to my house, I had a little laugh at the sheer amateur nature of this con game.

However, as I was about to toss Bruno’s letter into the garbage, I had a sudden realization. This scam must work on someone, or the fraudsters wouldn’t go to the trouble of paying postage to mail it.

So, although the letter was certainly suitable for the trash can, I decided to bring it into my office instead. I had a little investigating to do about Peter Bruno, his “law firm,” and my husband’s impending jumbo inheritance.

The inheritance scam begins with an unsolicited “proposal”

Back at my desk, I had a closer look at the scammer’s proposal.

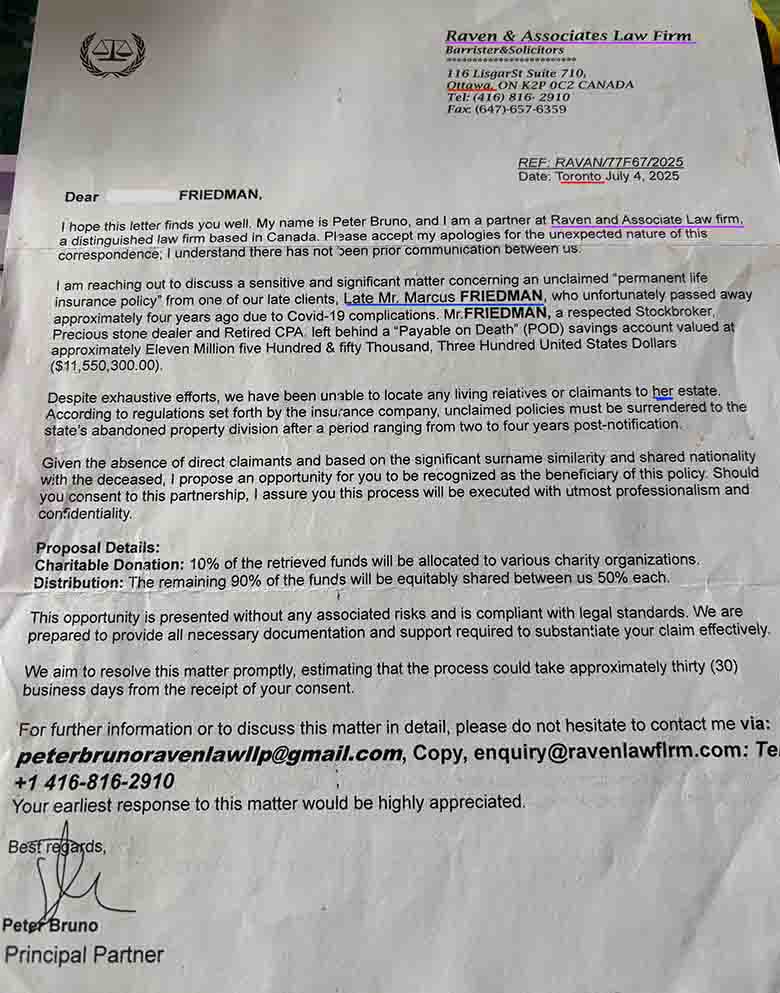

I noticed immediately that Bruno’s confusion wasn’t limited to geography. Not only was he unsure of the law firm’s location, but also unclear about the very name of the business.

Bruno identified himself as the Principal Partner in “Raven and Associate Law Firm,” a self-described “distinguished law firm in Canada.” But his letterhead names the law firm as Raven & Associates Law Firm. A slight difference, but certainly not a mistake the “Principal Partner” of a law firm would make.

The letter went on to explain that my husband could inherit an “unclaimed permanent life insurance policy” from Bruno’s late client. Additionally, there was the matter of something called a Payable on Death (POD) savings account. That was where the bulk of the money was located — $11,550,300.

Sadly, though, his multiple full-time careers seem to have left him no time to forge a family life. Nor did he leave behind any close friends. So his heap of cash had been sitting for years in a Payable on Death (POD) savings account with no beneficiary.

“Despite exhaustive efforts, we have been unable to locate any living relatives or claimants to her [sic] estate,” wrote Bruno, misgendering his client.

And so, logically, Bruno had tracked down a random guy named Friedman in the United States to inherit his client’s fortune.

What’s a Payable on Death (POD) savings account?

Scammers often speak in gobbledygook – a hodgepodge of words and phrases with random legal terms sprinkled about meant to confuse potential victims. And because many bad actors are operating from abroad and don’t speak fluent English, grammatical errors are common.

Bruno certainly was writing in the language of his cohorts. The complex explanation of how my husband could be eligible to inherit Marcus Friedman’s savings account was flawed at its core.

Fact: A Payable on Death (POD) savings account makes it easy for the named beneficiary to receive the funds upon the death of the account holder. The cash inside a POD does not pass through the estate, instead it is automatically transferred to the beneficiary. In order to create a POD, there must be a named beneficiary.

Yet, Bruno’s narrative implied that his client had somehow managed to create a POD with no beneficiary. The suggestion that a total stranger could inherit a POD four years after the account holder’s death was nonsensical and impossible.

Of course, he’s literally banking on the fact that his intended victims don’t know this.

Scammers are looking for targets who are unfamiliar with the terms they’re spitting out. The success of their schemes depends on keeping their prey in the dark and closing the deal quickly before their victim realizes what’s happening.

Predictably, Bruno was eager to get the process rolling, anticipating the transaction would take about 30 business days.

And although his proposal included a provision to donate 10 percent of the $11,550,300 to charity, his ultimate goal wasn’t exactly benevolent. Bruno intended to keep more than $5 million for himself.

How the inheritance scam victimizes its target

If you’re a regular reader of Consumer Rescue, then you know that this isn’t the first time my family has been informed of impending riches.

A friendly, self-described “Man of God” recently called to inform me that I had won $5 million in the Publishers Clearing House Sweepstakes. In that call, which I recorded, you can hear the fraudster joyfully giving me the good news. According to him, he would soon be on my doorstep delivering that big check along with a big hug.

This scammer was hoping I wasn’t aware that PCH had filed for bankruptcy earlier this year. Or perhaps he wasn’t even aware that the company had collapsed. He just needed “one percent of my trust,” he assured me… as he attempted to extract personal details, including my bank account information.

The goal(s) of the inheritance scam are quite similar to the PCH scam:

- To steal the identity of the victim

- To convince the victim to “pre-pay” fees and taxes in order to receive the inheritance

I attempted to call Bruno and find out how much it would cost to process my husband’s inheritance. Unfortunately, I waited too long. The letter sat on my desk for a few weeks before I called Bruno’s number. By then, it was disconnected.

Scammers often change their contact information after a successful con so that they’re unreachable. Bruno’s disconnected phone number suggested to me that he likely snagged at least one victim from this scheme.

📬 Subscribe to:

Tales from Consumer Advocacy Land

Real stories. Real rescues. Real advice.

Join thousands of smart travelers and savvy consumers who already subscribe to Tales from Consumer Advocacy Land — the friendly weekly newsletter from Michelle Couch-Friedman, founder of Consumer Rescue. It's filled with helpful consumer guidance, insider tips, and links to all of our latest articles.

Related: Beware the government grant scam. That is not your Facebook friend

Who falls for the inheritance scam?

My first impression when I read this letter was that no one could possibly fall for this scam. The writing is clunky and filled with errors. The premise is absurd.

But people have repeatedly fallen for the inheritance scam, collectively losing millions of dollars to these bad actors.

Like many scams, this one targets a vulnerable population: elderly men and women.

Related: Why is Keto Supplement customer service calling to tell me I owe big money?

The Department of Justice brought charges against a group of men based in Spain which targeted elderly Americans for the inheritance scam. Court documents showed that over the course of five years, the criminals extracted over $6 million from 400 victims.

According to the indictment, those individuals mailed letters through the USPS to large swaths of elderly people in Florida.

.…the defendants told a series of lies to consumers, including that, before they could receive their purported inheritance, they were required to send money for delivery fees, taxes, and payments to avoid questioning from government authorities. The defendants collected money sent in response to the fraudulent letters through a complex web of U.S.-based former victims, whom the defendants convinced to receive money and forward to the defendants or persons associated with them. According to the indictment, victims who sent money never received any purported inheritance funds.

(Press release from The Department of Justice)

Based on the letter I found in my mailbox, delivered by the USPS, we can assume that the inheritance scam is alive and well. Its home base has just moved from Spain to Canada.

Related: Travel agent arrested and charged with grand larceny

What to do if you or a loved one has already fallen for the inheritance scam

If you have a loved one who is in the target population for the inheritance scam, it’s important to familiarize them with this scheme. For someone who isn’t looking carefully or doesn’t know what to look for, this letter could be convincing.

The 400 victims named in the Department of Justice’s indictment prove that this scam is sometimes successful. If you have already fallen prey and handed over personal information or money, it’s essential to protect yourself from further victimization.

Related: Help! A LinkedIn job scam cost me $9,000

1. Report the crime to the authorities

There are two primary organizations where a victim of an inheritance scam should file a report: The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). I recommend making a report to the victim’s local police station as well. Often, scammers target communities — especially those with similar demographics. Local authorities can issue a community alert.

2. Call the National Elder Fraud Hotline

The Department of Justice’s National Elder Fraud Hotline, 1-833-372-8311, is a valuable resource for victims or targets of the inheritance scam.

3. Enroll in an Identity monitoring program

One of the primary goals of this scam and similar scams is to steal the victim’s identity. If the victim has given personal information to the scammer, such as their bank account details, credit card, or Social Security number, it’s crucial to enroll in an identity monitoring program. Your credit card company or bank may offer a free or low-cost identity protection feature for fraud victims. You may also be advised to place a freeze on your credit reporting accounts at Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax.

4. Inform your bank and credit card companies

As with any scam, if you’ve shared your bank account or credit card number, alert the company immediately. In some cases, you can prevent the bad actors from accessing your money if you block them quickly enough.

The bottom line

Remember, even though this scam may not be something you could fall for, someone you love might be vulnerable. With a little pre-emptive warning about the inheritance scam and other schemes like it, we can head these bad guys off at the pass. And that’s a very good thing. (Michelle Couch-Friedman, Chief Fiasco Fixer and founder of Consumer Rescue)

You might also like: 8 costly rental car scams and mistakes to avoid this year

Don’t forget: It’s okay to ask for help. Consumer Rescue is here for you 24/7. Use the button below to ask for our free advocacy assistance.